Auf Messers Schneide (1946)

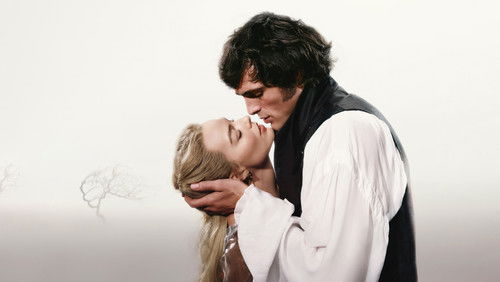

51KAuf Messers Schneide: Directed by Edmund Goulding. With Tyrone Power, Gene Tierney, John Payne, Anne Baxter. An adventuresome young man goes off to find himself and loses his socialite fiancée in the process. But when he returns 10 years later, she will stop at nothing to get him back, even though she is already married.

“The Razoru0026#39;s Edge (1946)u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eA stately, dramatic, richly nuanced film about love, true love, and the love of life. Itu0026#39;s about what matters, and what doesnu0026#39;t, in a high society world George Cukor could have filmed, but this is by director Edmund Goulding, coming off of a series of war films, and with the great Grand Hotel from 1932 in his trail. Some people will find this a touch stiff or slow, or rather too nuanced, but I think none of the above at all. It has the richness of the Somerset Maugham novel it is based on, and Goulding had just filmed (the same year) Of Human Bondage, another Maugham novel. In both cases, the writer contributed to the screenplay, and the combination of the two of them seems really perfect. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eTyrone Power is an interesting lead man, as the idealistic and handsome Larry Darrell, and in some ways his restraint and almost studied dullness at times is maybe what the film needs for its rich, calm trajectory through the twenty years it covers. Heu0026#39;s as stable and u0026quot;goodu0026quot; as the wise, knowing figure of the author, who appears in the form of actor Herbert Marshall. Gene Tierney as Poweru0026#39;s counterpart and eventually counterpoint plays the spoiled woman with cool, dramatic perfection. Sheu0026#39;s got energy and edge and beauty from every angle, and she maintains just that slightest duplicity in every scene, so you are kept on your toes.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe only forced and almost laughable section is the one that demands we think profound thoughts…the guru in India being guru to our hero. Unfortunately, it lasts for fifteen minutes, and though there is a spiritual necessity to the experience he has there, this spiritual aspect is implied just as fully in the worldly scenes that follow. I can picture a far better movie without this insert, and I can picture the director picturing it, too. Someone knows why it got patched in, and for whom, but this is what we have. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eIt has to be said the filming, as conservative as it is in many ways, is spot-on gorgeous. The brightly lit, ornamented, busy sets are actually inhabited by the camera, and the figures move together not only across the field, but front to back as well, in triangles and curves of visual activity, yet with fluidity–itu0026#39;s all contained and lyrically delicious. This is done without ostentatious mood, without sharp angles and bold lighting, but instead with spatial arrangements, always full, no emptiness, no great shadows, always something more to see. A great example, easy to find, is the very last scene, just before the shot on the boat when the end titles run. Watch how Marshall walks the long way around Tierney, and then she walks around him, and the camera keeps them framed side to side, front to back. Itu0026#39;s nothing short of brilliant, and yet, in style, so different than say Toland doing Kane or, at another extreme, Ozu doing Tokyo Story. But no less spectacular.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAt one point, a minor character, a defrocked priest, says to Darrell in a working class bar, u0026quot;You sound like a very religious man who does not believe in God.u0026quot; The movie is really about godliness, or what Maugham calls u0026quot;goodnessu0026quot; in the end. And some people have it, and share it, and make the world better, God or no God.”