Das Rad (1923)

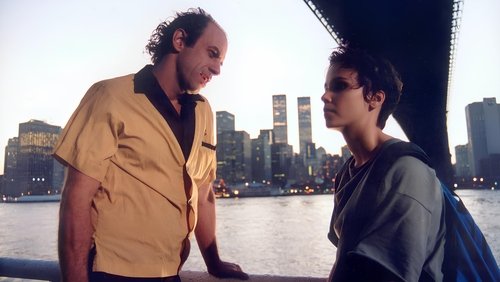

7KDas Rad: Directed by Abel Gance. With Gabriel de Gravone, Pierre Magnier, Georges Térof, Séverin-Mars. A railway engineer adopts a young girl orphaned by a train crash. Years later when she starts getting suitors, he grapples with whether or not to tell her the truth about her parentage.

“Okay, as I am discovering, the name of Abel Gance as has reached us through a long and troubled historiography is mostly in the contours of a European DW Griffith; the broad historic scopes, the elaborate film language. But whereas Griffithu0026#39;s pioneering efforts were narrowed by a set of Victorian ideals about a world where good and evil are clearly defined and the prevalent Western thinking that has traditionally regarded the struggle between these two fractions in rational, linear terms as the forward struggle of human thought to achieve enlightenment from the forces of darkness – the forces of production or state morals for Griffith – Gance foresaw deeper: objects cast their shadow here, human beings have interior dimensions, and the darkness no longer threatens from outside but is recast inside the human character.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThis is the film that Kurosawa fondly remembered as one of the first to impress him. So, a film that resonated within Japanese culture of the time, a culture that has increasingly sought out and adopted – long before the westerns of John Ford – Western perspectives in their traditionally abstract eye.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eBut the more obvious stuff before we get there, how the film must have equally well impressed the early Soviet filmmakers. There may not be crowds animating, acting out rigorous ideals – not history as in Griffith, but present action, history in the making – but there is a shift; the Shakespearian tragedy, and thus the cleansing, high-minded catharsis, now transferred to the working class, so that the new Oedipus, the new Lear or Sissyphus, the new king punished with divine madness becomes the insignificant railroad engineer – named Sisif no less – with the perennially greasy, coalblack face. It is now the lowly and disenchanted whose life agonies can be imbued, and given voice to, with the majesty of a world ruler; hence the ruled world, the kingly dominion, is reordered as the private life of organized anxieties.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSo, this part of the film should bode well with a contemporary audience, who can also better acquiesce to the idea of a film that runs for 4 1/2 hours. But there is stuff that matters more, I believe.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSee here. Sisifu0026#39;s house is situated where the tracks converge and disperse from again, so at the navel of the soul. At regular intervals fates depart from there – some of them the desperate attempts to destroy the self, others harboring omens or disaster.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eBut once up in the exile of the mountains, the house – now the hermitage, the temple of atonement – is where the tracks lead and stop. There is no going further, and there are some amazing shots of snowed mountain peaks captured from a moving train that you will want to see. Here, the protagonists must struggle with a karma that is not possible to extricate without the dissolution of the self that is the essence of spiritual transformation.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe poignant image that unifies vision; wheels, wheels turning fates in the incessant cycle of life-renewing destruction. The Soviets appropriated this image – as well as the rapid-fire montage pioneered here by Gance – as a representation of social mechanisms at work; but here the image is properly internal, in-sight into abstract soul.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe heartfelt denouement is about the last – and hence, first – turn of the wheel, the cosmic round of succession of an impermanent, transient universe. Itu0026#39;s all pretty obvious at this point, which maybe derails the more powerful metaphors into a typically classical story end.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSo this is probably why the film spoke with clarity to the Japanese, whose world is not linear but vivid impressions from a birdu0026#39;s eye. At the end, a circle of young girls and boys dance away in the shadow of the mountain; like in so many Japanese landscape paintings where idyllic everyday pleasures among the cherry-blossomed trees unfold beneath the distant horizon of Mt. Fuji.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eGance shows how the final release from the round can only begin with the acceptance of suffering. It is a Buddhist image, whereby this darkness recast inside the human character is finally understood to be no different from light.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eWe may encounter it in a jodo temple as the bodhisattva Kannon-Avalokitesvara, who reconciles both male and female form – and so all human disparity – in singular, unbound mercy; the name in her female form, poignantly as ever with the Japanese rendered into picture language, means u0026#39;Observing the Sounds (or Cries) of the Worldu0026#39;. So, not the person who observes, but the act, the living process of the round – filled with the cries of suffering – as it comes into being and goes again.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAsides into meditation. But the film is boss as is.”