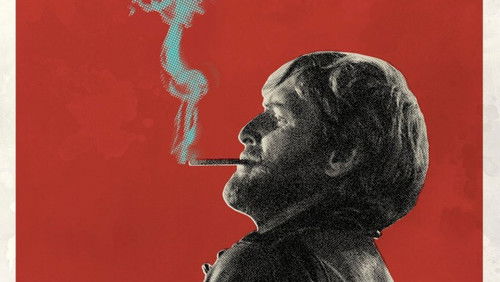

Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray (2009)

66KDas Bildnis des Dorian Gray: Directed by Oliver Parker. With Ben Barnes, John Hollingworth, Cato Sandford, Pip Torrens. A corrupt young man somehow keeps his youthful beauty eternally, but a special painting gradually reveals his inner ugliness to all.

“If one is titillated by the filmu0026#39;s actually boring visuals – stage design excepted and congratulated – then I must say one is really duped into believing that opulent visual description is film-making and that u0026quot;debaucheryu0026quot; displayed is really transgressive. It is also a total misconception of what the book is really about.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSo, letu0026#39;s unpack some things. Some people say that the book hinted because the times did not allow full-blown depictions concerning sexual matters. Wrong. Oscar Wilde was quite clever to know that hinting at…those things was actually more effective. It just takes a hint for Victorian prudishness to get heated by its unassumed imaginings. This seems does not go for our times: some get lured into believing that graphic depiction means surmounting a censoring obstacle, while this in truth falls flat. Hitchcock knew that playing with identification, expectation, the frustrations of the imagination was more sexual than shots describing sex. Or Kubrick: some reviews mentioned his u0026quot;Eyes Wide Shutu0026quot;, and for the sexual orgy scene as something clumsy and laughable. Wrong again. Kubrick rather wanted to show that a luxurious elaborate orgy is actually rather cold and boring. Sex cannot be directly pictured. It is a matter of representation, and, even more, its gaps and discontinuity. That is where we really invest, where our fantasies lie, and tell the truth.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe problem lies not in how one should depict the underlying sinister atmosphere of the novel concerning sexual matters. The lead has no charisma at all: he plays Dorian Gray as Harry Potter. Colin Firth is good in a misconception of his character. As Wilde himself wrote Lord Henry is his reflection u0026quot;as the world thinksu0026quot; he is. Colin Firth played the part without any of the delicious sarcasm this would demand. Et cetera et cetera for the rest of the cast. It all is irrelevant.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eIrrelevant because this is not the nature of the book: the book has a very peculiar quality that is difficult to pin down. It is a take on the Faustian myth. It is part of the decadent movement. It is Gothic, it is aesthetic. All that it may be, it is something else. It is rather a writersu0026#39; book for its themes are mimesis, or imitation, and influence.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eOscar Wilde is one of a handful of great thinkers on matters of (literary) influence, and this is the main tension that propels the book onward, contrasting with a rather catholic concept of sin, and bursting with the conceptual inversion of mimetic principles. Lord Henry is the representative of influence, a socialite luring Dorian Gray into paradox. How can one live in such times? he seems to say. Well, by living in paradox. Paradox is here for us, is our natural environment. It would go to lengths, elaborating on nuance, anxiety, and in general the tropes on which the book relies, making it a permanent read beyond its moralistic, or corrupting, surface, but this much is sure: Oscar Wilde knows that influence, as fantasy, could be equally frustrating and liberating. Influence and fantasy mean we are not Adam, first thing in the morning, for better and worse. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eOr, in another way, Dorian Gray suffers from an imbalance between himself and his mirror image: the price to be paid for retaining his image in all its harmonious consistency is that the entire horror of its amorphous leftover falls to him. This amorphous leftover is the material correlative to the gaze. For all the good influential paradoxes of the world, not until the very end does he abandon his image. The film did not catch any of that. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe book is also stuffed with lengthy chapters about artistic specimens Dorian Gray impulsively collects, making it something of a period piece. And this is where the film resembles the book in its most unfortunately hilarious.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAlthough not one iota of this is represented in the film, it strikes quite a note: as in the end of the 19th century prevalent, period preoccupations were presented with, say, an u0026quot;imperially informedu0026quot; innocence, so the decadent movement (portions of the book read as takes, critiques and elaborations on Pater and Ruskin, that is why it risks being something of an inside, undramatic joke) displayed a style of journalistic mannerisms and purple prose – so does the film exemplify respective aesthetic misfires: an (M)TV aesthetic, soft-porn libertinism, same old horror in the attic, into an unimaginative pile, thus showing its lackluster take on mimesis. The photography fails to establish a consistently sinful look: it should insist on, for example, that ebony sinister quality of the hall that leads to the attic. Where is the booku0026#39;s opium polish? The ashen look, when the portrait happens to look at the outside world is good, but whatever ambiance it aspires to, tumbles down when we are shown the portrait in the end, which actually looks like a parody of a damned Pirate of the Caribbean.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eItu0026#39;s a pity because with intelligent elaboration the daughter-of-Lord-Henry theme could yield to a really good take on a certain kind of neo-Darwinism by introducing tension to the theme symbolic child via influence vs biological child as responsibility; but in the end it ludicrously becomes another take on familial-ties-must-remain-strong. And it so resembles the booku0026#39;s dated, absent from the film, lengthy and inconsequential parts. The film is absent from itself, locked somewhere up in an attic of clichés.”