Che: Part Two (2008)

67KChe: Part Two: Directed by Steven Soderbergh. With Demián Bichir, Rodrigo Santoro, Benicio Del Toro, Catalina Sandino Moreno. In 1967, Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara leads a small partisan army to fight an ill-fated revolutionary guerrilla war in Bolivia, South America.

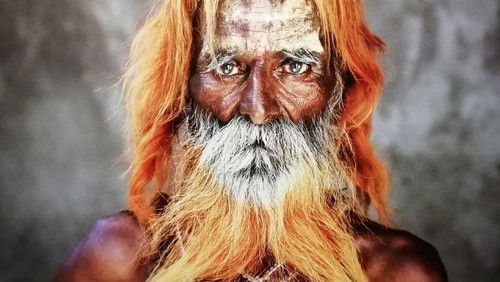

“It helps to know that this was originally brought to life as a Terrence Malick screenplay about Cheu0026#39;s disastrous forray in Bolivia. Financing fell through and Soderbergh stepped in to direct. He conceived a first part and shot both back to back as one film trailing Cheu0026#39;s rise and fall.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eHe retained however what I believe would be Malicku0026#39;s approach: no politics and a just visual poem about the man behind the image, exhaustive as the horrible slog through Cuban jungles and windswept Andean plateaus must have been. Malick applied this to his New World that he abandoned Che for, lyrical many times over.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eBut Soderbergh being an ambitious filmmaker, he puzzled over this a little more. Here was a man of action at the center of many narratives about him, some fashioned by himself, conflictingly reported as iconic revolutionary or terrorist, charismatic leader or ruthless thug, erudite Marxist thinker or brutal soldier.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSo how to visually exemplify this contradicting ethos as our film about him? And how to arrange a world around this person in such a way as to absorb him whole, unfettered from narrative – but writing it as he goes along – off camera – but ironically on – and as part of that world where narratives are devised to explain him. As flesh and bones, opposed to a cutout from a history book.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eOne way to do this, would be via Brecht and artifice. The Korda photograph would reveal lots, how we know people from images, how we build narratives from them. Eisenstein sought the same in a deeper way, coming up with what he termed the u0026#39;dialectical montageu0026#39;: a world assembled by the eye, and in such ways as the eye aspires to create it.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSo what Soderbergh does, is everything by halves: a dialectic between two films trailing opposite sides of struggle, glory and failure, optimism and despair. Two visual palettes, two points of view in the first film, one in the presence of cameras hoping to capture the real person, the other were that image was being forged in action.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe problem, is of course that Brecht and Eisenstein made art in the hope to change the world, to awaken consciousness, Marxist art with its trappings. By now we have grown disillusioned with the idea, and Soderbergh makes no case and addresses no present struggles.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eBut we still have the cinematic essay about all this.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe first part: a narrative broadcast from real life, meant to reveal purpose, ends, revolution. The second part: we get to note in passing a life that is infinitely more expansive than any story would explain, more complex, beautiful, frustrating, and devoid of any apparent purpose other than what we choose as our struggle, truly a guerilla life.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eI imagine a tremendous film from these notions. Just notice the remarkable way Part 2 opens. Che arrives at Bolivia in disguise, having shed self and popular image. No longer minister, spokesman, diplomat, guerilla, he is an ordinary man lying on a hotel bed, one among many tourists. Life could be anything once more, holds endless possibility. Cessation.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eWhat does he do? He begins to fashion the same narrative as before, revolution again. Chimera this time. Transient life foils him in Bolivia. Instead of changing the world once more, he leaves behind a story of dying for it. We have a story about it as our film, adding to the rest.”