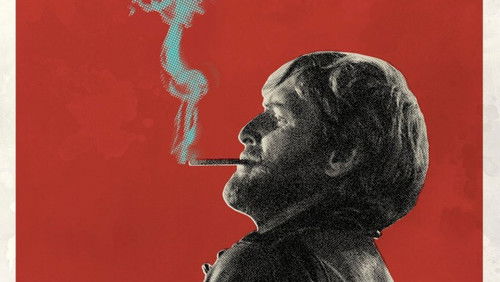

Die Privataffären des Bel Ami (1947)

13KDie Privataffären des Bel Ami: Directed by Albert Lewin. With George Sanders, Angela Lansbury, Ann Dvorak, John Carradine. Writer Georges Duroy (George Sanders) is one social-climbing S.O.B. who does most of his climbing over the warm (and cold) bodies of women. He begins with Rachel (Marie Wilson), a hanger-on in the cafés and Folies Bergere crowd, and then moves on to dally with Clotilde de Morelle (Dame Angela Lansbury). Always striving to move upward on the social scale, he ditches her to marry Madeleine Forestier (Ann Dvorak). Now he gets on the fast track. He persuades Madame Walter (Katherine Emery), the wife of his publisher, to fall in love with him, and then compromises Madeleine to frame a divorce, so he can pursue Madame Walter’s daughter, Suzanne (Susan Douglas Rubes). He moves along so well that ere long he is in legal position to usurp the title of one of France’s most noble houses. The moral, at the end, is it is okay to mess with French women, but triffling with French titles is going too far.

“Director Lewin started out on his own with a trio of literary adaptations: Somerset Maughamu0026#39;s Moon And Sixpence (1943) was followed by Oscar Wildeu0026#39;s The Picture Of Dorian Gray (1945), and then came this version of Guy de Maupassantu0026#39;s best novel, Bel-Ami, in 1947. George Sanders appeared in all three, giving each a distinct flavour by his presence. A self-obsessed and destructive individual appears in all, increasingly prepared to isolate himself from conscience or morality in order to achieve his goals – at least until an ending brings some comeuppance or resolution. In the first, Sanders plays a Gauguinesque painter, who deserts his family to work in Tahiti. In the second, Dorian Gray pursues his famously immoral activities, Sanders in attendance, whilst Grayu0026#39;s famous painting grows ugly in the attic. In The Private Affairs Of Bel Ami (aka: Women Of Paris, 1947), Sanders returns to centre stage portraying a man climbing to social success over a succession of suffering women.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eScriptwriter-director Lewin brought to each of these films characteristic qualities: literate dialogue, visual excellence, and a representation of interior states through colourful moments of art among them. In the fin de siècle worlds of Dorian Gray and Bel Ami, Lewin sharpens the unease and implicit questioning of mores shown in his earlier Maugham adaptation. Avoiding the temptations of melodrama, he chooses specific historical milieu by which to communicate the ennui of the privileged and the corrupt. Sanders is excellent as George Duroy, the titleu0026#39;s charming and unscrupulous social climber, who cannot be trusted with hearts – or come to that, much else: one in the words of the title song who u0026quot; will be leaving me, (and) who will be deceiving me..u0026quot; First seen down to his last few francs in 1880u0026#39;s Paris, Duroyu0026#39;s suave looks continually make him irresistible to women have brought him little in the way of fortune. Offered a chance job in journalism by his ex-army friend Forestier (John Carradine), Duroy asks Forestieru0026#39;s independently minded wife Madeline to help with the creation of a first article, while also entering into a relationship with the far more doting Clotilde (Angela Lansbury). Soon the seductive antihero is on his way up the social scale after marrying Madeline (a suggestion he promptly broached in the hapless Forestieru0026#39;s death chamber). Later after engineering a scandal, he divorces this first wife, and acquires a defunct aristocratic title with a view to moving on and up again.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eu0026quot;Youu0026#39;re a sneak thief… you take advantage of everyone, you deceive everyone,u0026quot; is the way the disillusioned Clotilde eventually personifies Duroy towards the end of the film, after he callously steals her heart, another manu0026#39;s wife and half her inheritance, then the family name of a missing heir, and finally inveigles the hand of a rich innocent. This single-minded obsession in reaching the top of the social ladder echoes that of the ambitious Horace Vendig in Ulmeru0026#39;s Ruthless, made the following year. Duroyu0026#39;s manipulative, seductive charm brings echoes too of Chaplinu0026#39;s Monsieur Verdoux, also from 1947. But while Duroyu0026#39;s progress does not directly lead to murder, it is more detestable and insidious. Whereas at the close of his film Verdoux offers disingenuous apology for his actions, Bel Ami (although saddled with a ending more in line with the demands of the censor than the original novel) is unrepentant, equating his final misfortunate as being u0026quot;scratched… by an old cat.u0026quot; There are several elements that make Lewinu0026#39;s film interesting today, being the independent work of a minor, if idiosyncratic auteur, then relatively unusual. Even though the aspirational cad makes use of the women he gets to know, Madeline remains a strong and talented character in her own right. Besides helping Duroy with his writing at the very start, there is a strong suggestion that she has actually been doing much of her first husbandu0026#39;s journalism for him too. And despite her final betrayal, she continues to impress as an individually motivated female, in contrast to the ever-loving and forgiving Clotilde. Both are victims but Duroyu0026#39;s emotional abuse and subjugation of them and others is a comment on his own coldness as well as on the liabilities of females in a prejudiced society, made especially keen by the knowledge each woman has of her own predicament. For men, the answer to honour slighted is a duel. Women at best are obliged to fall back on subterfuge or, at worst, live with the grief of a broken heart.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eEach of Lewinu0026#39;s first three films was made in black and white. But they also included moments when the screen bursts into startling colour, as the audience contemplates painting central to the theme. The Moon And Sixpence brings a final sequence showing the artistu0026#39;s work, a form of artistic justification for preceding events. In The Portrait Of Dorian Gray, the painting in question reflects back directly the moral dissolution of the subject. Bel Amisu0026#39; canvas occupies a more complex position in its narrative than its predecessors. Itu0026#39;s an expensive work of art, bought by a wealthy patron and admired by Duroy, – one of the few moments in which, half to himself, he evidently expresses an honesty with anything. Painted by Max Ernst (his Temptation Of St Anthony) it reflects back the decadence of its admirers, as well as continuing the plotu0026#39;s subtle thread of damnation.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAn excellent cast includes a young Lansbury as Duroyu0026#39;s one true love, and John Carradine as his tuberculosis-ridden journalist friend. Audiences today will be impressed by how modern the feel of it all is, whether in the depiction of Duroyu0026#39;s amoral, manipulative character, completely unfazed at being disliked, or the filmu0026#39;s sophisticated and sympathetic treatment of women. Lewinu0026#39;s next work was the weirdly romantic Pandora And The Flying Dutchman (1951), his most ambitious film, the reception of which proved a disappointment. He never rose to such heights again. The Private Affairs Of Bel Ami, is less flamboyant perhaps but just as unforgettable, remaining his most satisfying work.”