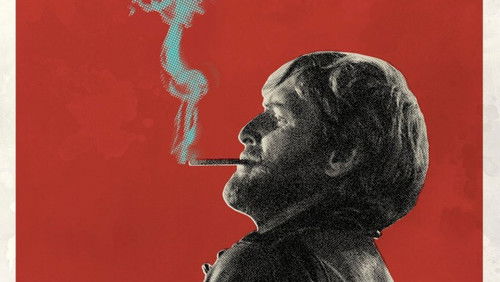

Großrazzia (1954)

15KGroßrazzia: Directed by Jack Webb. With Jack Webb, Ben Alexander, Richard Boone, Ann Robinson. Two homicide detectives investigate the brutal shotgun murder of a crime syndicate member.

“Were the u0026#39;fifties really this awful? The mind boggles.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eMoviegoers in 1954 got excited when they heard that one of their favorite TV shows, Dragnet, had been made into a feature film. (I remember because I was one of them.) One now stares in wonder at this icon of the strange and far-off u0026#39;fifties, an era that was Eisenhower-sunny on the surface and dark and menacing just beneath it.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eDragnet the movie (eventually there was a second, on TV), now largely forgotten, was nothing more than an extended television episode made in color, while home sets were still black and white. Judging from the pictureu0026#39;s low-rent set-ups, it must have been one of Warner Brothersu0026#39; most cheaply made films for that year. A couple of scenes take place in empty fields, and—with the single exception when filming was done at the African wing of the Los Angeles County Museum—the indoor sets were not much more imposing. Many of the actors were frequently unemployed second-string players whose work did not make a deep impression.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eIn the intervening time since it was made the film has largely gone unseen and although it made it to video, it is little viewed in this form. (I found a dusty copy at a Half-Price book store, selling for a desperate-to-get-this-turkey-off-the-shelf $3.99!) Predictably, it has dated badly. That u0026#39;fifties audiences accepted the actorsu0026#39; rigidly stylized, robotic impersonations of police officers as representing the way they actually spoke in real life says something about Americansu0026#39; willingness to uncritically accept virtually anything they saw in movies, and especially on TV. (Remember actors posing as doctors extolling the pleasures of smoking during cigarette commercials?) Dragnetu0026#39;s copsu0026#39; signature manner of speaking—a flat, semi-technical, bureaucratic argot, spoken in low, monotonal voices—Webbu0026#39;s cops rarely if ever snarled—was one of the most memorable things about the show. Now this is seen for what it always was: unintentional self-satire. (On the other hand, to Webbu0026#39;s great credit, virtually all modern-day cop shows stemmed from Dragnet, untold imitations of which have been launched on television over the past five decades)u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eFor more evidence of the filmu0026#39;s antiquated point of view, watch the scene at the jazz club where Friday and Smith, seeking information about a criminal theyu0026#39;re pursuing, converse with a musician whou0026#39;s one of their informants. Thereu0026#39;s a humorous moment when Smith gets a `real hipu0026#39; handshake from the trumpet player that is nothing more than a quick swipe and a handful of air, then stares at his hand as if to figure out what had just transpired. This is followed by a three-way conversation during which the script clumsily has the musician work his way through an A to Z litany of now-moldy, u0026#39;fifties hipster clichés (`Howu0026#39;s that chick?u0026#39; `Really flipped, huh?u0026#39; `Oh man, thatu0026#39;s a drag,u0026#39; `He was really nowhere,u0026#39; `Iu0026#39;ve been digginu0026#39; it in the papers,u0026#39; `He was jumpinu0026#39; pretty steady with that Troy mob,u0026#39; `Dig ya.u0026#39;) by way of what the screenwriter apparently must have regarded as establishing a well-rounded character.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eNot only was the film disappointing in how little attempt was made to `open it upu0026#39; for the big screen, but in some ways its narrowly focused two-for-a-nickel script was decidedly less interesting than what was shown on the television show. For example, it missed interesting possibilities for character development, especially as this pertained to Webbu0026#39;s Joe Friday and Ben Alexanderu0026#39;s Frank Smith. (Some time after the filmu0026#39;s debut, Webb finally recognized that television viewers yearned to know more about Joe Friday in his off-duty hours and so gave them glimpses of this law enforcement automatonu0026#39;s meager social life, including intriguing little dabs of romance.)u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe film version also completely wastes the participation of Ben Alexander, the warmest and most appealing of all Joe Fridayu0026#39;s sidekicks, leaving him with nothing to do except dutifully tag along with his superior officer and occasionally asking suspects or witnesses the odd question or two. The inspired daffy non sequiturs that his character, Frank Smith, regularly voiced in conversations with Joe Friday on the television show, which viewers loved and looked forward to, were almost entirely absent from the film. The one exception, which occurs during a brief back-and-forth with Webb about their individual food preferences, is so brief and isolated that it comes off as a self-conscious sop to audiences whom the screenwriter knew would be looking for it and falls flat.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eWebb also was the filmu0026#39;s director, and he went about most of these duties with a notable lack of imagination. The result is a picture that is dreary and monotonous from start to finish. He elicited almost uniformly wooden-and even occasionally embarrassing-performances from the cast (leaving one to wonder how much of his own money was invested in the film or what his deal was with Warneru0026#39;s, and whether he might even have deliberately restricted himself to printing the first take, no matter much a second or even a third might have been desirable). The scene where as Joe Friday he interrogates the crippled woman whose small-time crook of a husband has just been killed is mawkish, and the actors playing police officers are directed to be so deadly serious that scenes like this were subsequently lampooned to great effect in the Dan Aykroyd satire made in 1987. At one point a very competent actor, Richard Boone, is reduced to miming a series of grotesque scowls while instructing his subordinates. Itu0026#39;s a wonder Webb didnu0026#39;t direct him to gnaw on a table leg.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eDragnet was a film that was mired deeply in its time and seems to evidence a disturbing subtext that relates to the American mindset as it was during the bland, conformist, and frightened Eisenhower/McCarthyite fifties. The Cold War was at its height in 1954 and fears by Americans of falling victim to communist manipulations and even outright mind-control were rampant. It may be no coincidence that Dragnet and Don Siegelu0026#39;s Invasion of the Body Snatchers appeared within two years of each other. The cops in Dragnet are not merely grim, intense, obsessed defenders of the law, they often border on being zombie-like. One of Dragnetu0026#39;s most explicit messages—brought home to audiences several times—was how, if only we didnu0026#39;t have so many laws and that darn Constitution, we could put a heck of a lot more criminals behind bars where they belong. Iu0026#39;ve replayed this film at least half a dozen times and each time I watched it, the scarier it seemed. Itu0026#39;s interesting to contemplate what super-patriot Joe Friday, if given the power and left to his own devices, would have done to lawbreakers. Luckily for the bad guys in the film—and possibly for all the rest of us—he wasnu0026#39;t given access to nuclear weapons.”