Was kommen wird (1936)

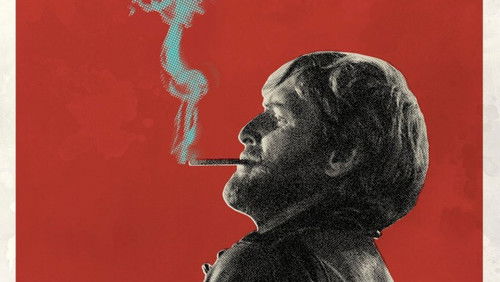

6KWas kommen wird: Directed by William Cameron Menzies. With Raymond Massey, Edward Chapman, Ralph Richardson, Margaretta Scott. The story of a century: a decades-long second World War leaves plague and anarchy, then a rational state rebuilds civilization and attempts space travel.

“I must admit a slight disappointment with this film; I had read a lot about how spectacular it was, yet the actual futuristic sequences, the Age of Science, take up a very small amount of the film. The sets and are excellent when we get to them, and there are some startling images, but this final sequence is lacking in too many other regards…u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eMuch the best drama of the piece is in the mid-section, and then it plays as melodrama, arising from the u0026#39;high conceptu0026#39; science-fiction nature of it all, and insufficiently robust dialogue. There is far more human life in this part though, with the great Ralph Richardson sailing gloriously over-the-top as the small dictator, the u0026quot;Bossu0026quot; of the Everytown. I loved Richardsonu0026#39;s mannerisms and curt delivery of lines, dismissing the presence and ideas of Raymond Masseyu0026#39;s aloof, confident visitor. This Boss is a posturing, convincingly deluded figure, unable to realise the small-fry nature of his kingdom… Itu0026#39;s not a great role, yet Richardson makes a lot of it.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eEverytown itself is presumably meant to be England, or at least an English town fairly representative of England. Interesting was the complete avoidance of any religious side to things; the u0026#39;things to comeu0026#39; seem to revolve around a conflict between warlike barbarism and a a faith in science that seems to have little ultimate goal, but to just go on and on. There is a belated attempt to raise some arguments and tensions in the last section, concerning more personal u0026#39;lifeu0026#39;, yet one is left quite unsatisfied. The film hasnu0026#39;t got much interest in subtle complexities; it goes for barnstorming spectacle and unsubtle, blunt moralism, every time. And, of course, recall the hedged-bet finale: Raymond Massey waxing lyrical about how uncertain things are! u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eConcerning the question of the film being a prediction: I must say itu0026#39;s not at all bad as such, considering that one obviously allows that it is impossible to gets the details of life anything like right. The grander conceptions have something to them; a war in 1940, well that was perhaps predictable… Lasting nearly 30 years, mind!? A nuclear bomb – the u0026quot;super gunu0026quot; or some such contraption – in 2036… A technocratic socialist u0026quot;we donu0026#39;t believe in independent nation statesu0026quot;-type government, in Britain, after 1970… Hmmm, sadly nowhere near on that one, chaps! 😉 No real politics are gone into here which is a shame; all that surfaces is a very laudable anti-war sentiment. Generally, it is assumed that dictatorship – whether boneheaded-luddite-fascist, as under the Boss, or all-hands-to-the-pump scientific socialism – will *be the deal*, and these implications are not broached… While we must remember that in 1936, there was no knowledge at all of how Nazism and Communism would turn out – or even how they were turning out – the lack of consideration of this seems meek beside the scope of the filmmakersu0026#39; vision on other matters.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eMuch of the earlier stuff should – and could – have been cut in my opinion; only the briefest stuff from u0026#39;1940u0026#39; would have been necessary, yet this segment tends to get rather ponderous, and it is ages before we get to the Richardson-Massey parts. I would have liked to have seen more done with Margareta Scott; who is just a trifle sceptical, cutting a flashing-eyed Mediterranean figure to negligible purpose. The character is not explored, or frankly explained or exploited, except for one scene which I shall not spoil, and her relationship with the Boss isnu0026#39;t explored; but then this was the 1930s, and there was such a thing as widespread institutional censorship back then. Edward Chapman is mildly amusing in his two roles; more so in the first as a hapless chap, praying for war, only to be bluntly put down by another Massey character. Massey himself helps things a lot, playing his parts with a mixture of restraint and sombre gusto, contrasting well with a largely diffident cast, save for Richardson, and Scott and Chapman, slightly.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eI would say that u0026quot;Things to Comeu0026quot; is undoubtedly a very extraordinary film to have been made in Britain in 1936; one of the few serious British science fiction films to date, indeed! Its set (piece) design and harnessing of resources are ravenous, marvellous. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eYet, the script is ultimately over-earnest and, at times, all over the place. The direction is prone to a flatness, though it does step up a scenic gear or two upon occasion. The cinematographer and Mr Richardson really do salvage things however; respectively creating an awed sense of wonder at technology, and an engaging, jerky performance that consistently beguiles. Such a shame there is so little substance or real filmic conception to the whole thing; Powell and Pressburger would have been the perfect directors to take on such a task as this – they are without peer among British directors as daring visual storytellers, great helmsmen of characters and dealers in dialogue of the first rate.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eu0026quot;Things to Comeu0026quot;, as it stands, is an intriguing oddity, well worth perusing, yet far short of a u0026quot;Metropolisu0026quot;… u0026#39;Tis much as u0026quot;sillyu0026quot;, in Wellsu0026#39; words, as that Lang film, yet with nothing like the astonishing force of it.”