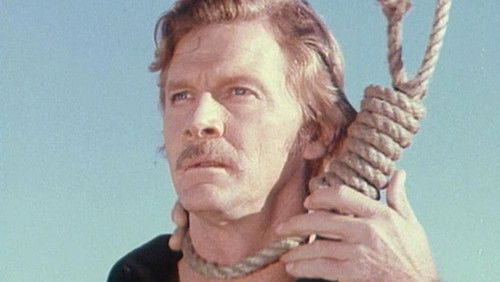

Wolf Lowry (1917)

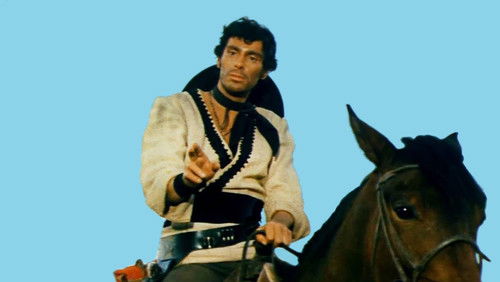

13KWolf Lowry: Directed by William S. Hart. With William S. Hart, Margery Wilson, Aaron Edwards, William Fairbanks. Tom “Wolf” Lowry, the owner of the Bar Z ranch, tolerates no intruders into his life. When he hears that settlers have entered his valley, he goes to confront them but has a change of heart when he sees Mary Davis, a young woman who has come West to find her missing sweetheart, Owen Thorpe. Mary nurses Lowry back to health after he is wounded by Buck Fanning, the real estate agent who sold Mary her claim, when Lowry prevents Banning from raping Mary. Lowry soon falls in love with Mary and she agrees to become his wife, having lost all hope of finding her former sweetheart. By coincidence, Lowry finds Owen, but when Owen and Mary meet and plan to run away together, Lowry insists that she honor her agreement to wed him. On the day of the wedding, however, Lowry has a change of heart and takes Owen and Mary to the minister and tells him to marry the two lovers instead. Lowry then leaves Mary a note saying that he is going to Alaska. Five years later, Mary and Owen are the parents of a young son, named Tom, and the recipients of a letter from Lowry who now lives in isolation in Alaska.

“I wanted to see this after a master class by composer Neil Brand for the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, where he demonstrated improvising musical scores to silent films by playing u0026quot;Wolf Lowryu0026quot; on his laptop while playing the piano. Not only an enlightening experience as to how piano scores are made today for these ancient titles, but it was also apparent that to do the job as well as Brand, one needs a deep understanding of silent cinema–even if itu0026#39;s something as simple as recognizing, so as to cue the appropriate music, that a well-dressed character with a mustache is probably the baddie in a William S. Hart vehicle. My only complaint was that he didnu0026#39;t finish the movie, but Iu0026#39;ve since been able to resolve that dilemma, from the restoration that was screened at the Bonn Silent Film Festival.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eItu0026#39;s a typical Hart Western, wherein he plays the good bad man whose regeneration is found in his love of an ideal woman. Itu0026#39;s not overtly Christian as with some of the others (although she is referred to as his u0026quot;idolu0026quot; at one point), and this is one of his more self-sacrificing roles. The love triangles also make it, perhaps, a bit more melodramatic, as well. Although itu0026#39;s not up to the standards of his best work–say, u0026quot;Hellu0026#39;s Hingesu0026quot; (1916), u0026quot;The Narrow Trailu0026quot; (1917), u0026quot;Wagon Tracksu0026quot; (1919)–just to see one of the most expressive faces in cinematic history at work, I could easily watch a dozen of his routine photoplays. Heck, I already have and likely will do so again.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe biggest drawback, as with many of these old films, is that even when they do feature racial minorities, it tends to be stereotypical and offensive. This one features Chinese characters in minor roles, the first instance of which is an awful gag involving a gang of white cowboys pretending that theyu0026#39;re going to lynch a Chinese man for stealing chickens. Later, Hartu0026#39;s character casually threatens one that if he tries to cheat him that, u0026quot;Iu0026#39;ll drag you across my range by the ears!u0026quot; In the master class, Brand demonstrated how he took the right approach in scoring today a film from yesteryear by not meeting the mock lynching scene on its own terms as a joke. Indeed, such is part of film history and shouldnu0026#39;t be hidden, but one neednu0026#39;t play along.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eOf course, the best part of u0026quot;Wolf Lowryu0026quot; is the actor, Hart, portraying the eponymous character. Besides his facial expressions, he exploits his imposing stature to make fun of Lowryu0026#39;s awkwardness around a lady–pouring most of a bag of sugar into his tea in one scene and tripping over a bucket of water in another. The film gets thematically dark by the final act, too. Early on, Wolf saves the woman, Mary, from an attempted rape and wouldu0026#39;ve killed the attacker had it not been for her intervention. As disturbing as this early encounter is to their eventual engagement, it turns out that Mary is afraid, as well as that of her attackeru0026#39;s, Wolfu0026#39;s violent streak. All of which makes for a bit more nuance than may be found in some more simplistic melodramatic fare from the silent era or movie history in general. The ending is especially well done, including a bride and groom whose lack of apparent enjoyment for a while reminds me of the ending of u0026quot;The Graduateu0026quot; (1967). Plus, this is one of those short, quickly–arguably too quickly–cut little features from the era thatu0026#39;s a breeze to get through.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAdditionally, although Mary, as the supporting love interest for the star, Hart, is a fairly standard and thankless role, except perhaps for her representation of a battered woman and her aforementioned abhorrence of violent men, the actress who played her, Margery Wilson, was more interestingly an early female director, as well as a writer, if only briefly during the early 1920s. Unfortunately, none of the films she directed are known to survive.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003e(Note: Film reconstruction from a 28mm Pathéscope safety print and two incomplete 35mm nitrate prints from the Library of Congress, with recreated tinting.)”