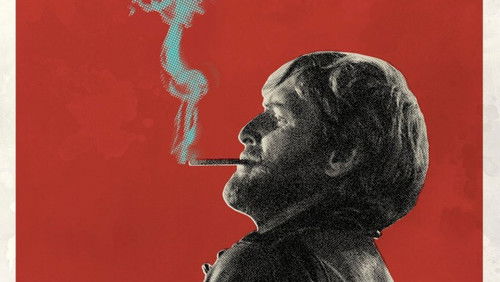

Forced March (1989)

31KForced March: Directed by Rick King. With Chris Sarandon, Renée Soutendijk, Josef Sommer, John Seitz. Ben Kline is a successful television actor looking for a meaningful role to make him a movie star. When he sets out to play a hero who died in the Holocaust, he is forced to face the reality of those victimized by the war. In assuming the role of Miklos Radnoti, who left a notebook of harrowing poems from his ordeal, Kline finds himself acting not as a hero, but rather a victim who speaks to us from the grave. As Ben gets ever deeper into his role, he begins to merge with his character, blurring the boundaries of truth and illusion. The realization for Ben, and for us all, is that the best homage we can pay to those who died is to understand them… to know that they had little choice in their fate. Everyone could not be a hero, but rather simply tried to survive as best they could, and that is the legacy of the six million.

“Chris Sarandon is inexplicably cast as a u0026quot;staru0026quot; here, an American actor cast in the lead role of a film against the directoru0026#39;s wishes, for box office appeal. Sarandon is an actor one could never accuse of being a star; heu0026#39;s competent but often too earnest and a little dull. Playing the Hungarian poet Miklos Radnoti, who we are told from the outset was killed during WW2, Sarandonu0026#39;s actor, Benjamin Kline, goes all method. He talks to himself in character, argues with the director about realism, demanding that he be actually tortured in one scene, sleeps on the set of a labor camp, and even gets a People magazine cover story u0026quot;The Method of his Madnessu0026quot;.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003enThe gimmick in the treatment is that we have a film within a film ie we see the film that is being made, edited and complete with music and voice-overs, and we also have the actors behind the scenes in modern dress. Sometimes the transitions are clever, though when Kline breaks out of character and we are jarred into another reality, the result is mostly camp. At other times, we have to check the costumes and hairstyles for the time frame, and there are vast canvasses and aerial views with no hint of the fictional directoru0026#39;s camera. However it helps that the director, Walter Hardy (John Seitz) seems even more of a egomaniac than Kline, at one point berating actors playing men about to be shot, for not being able to smell their fear. The funniest moment is when Hardy holds a gun to Klineu0026#39;s head (admittedly a prop gun) to get what he wants, but ultimately what undermines these scenes is our realisation that such behavior is nonsensical eg when the director is ranting, we think, where is the producer to remind him of the time being wasted?!u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe narrative includes oddities such as the door of a trainu0026#39;s cattle truck being left open when Jews are being shipped to the labor camp, a cut from a singeru0026#39;s yell to a train whistle, and bare breasted female dancers in contemporary Hungary for the entertainment of German tourists. The latter is interesting given that we are told that Hungary was a German ally, and that the guards of the Boor labor camp in Yugoslavia are Hungarians. The camps are also described as being like military service for Jews, which reads as rather patronising given that men are arbitrarily tortured and killed, just as in the concentration camps. We get the standard question of why didnu0026#39;t the Jews resist their fate, with the answer given that passivity has more dignity, and is luckier. Kline also has a personal history, where his Hungarian father only reveals the fate of his mother during the filming of his movie, though ultimately, this plot point is a red herring.”