Tokyo Drifter – Der Mann aus Tokio (1966)

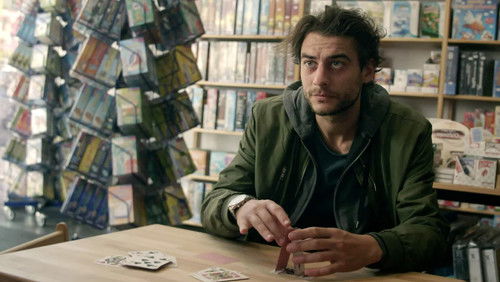

29KTokyo Drifter – Der Mann aus Tokio: Directed by Seijun Suzuki. With Tetsuya Watari, Chieko Matsubara, Hideaki Nitani, Tamio Kawaji. After his gang disbands, a yakuza enforcer looks forward to life outside of organized crime but soon must become a drifter after his old rivals attempt to assassinate him.

“Unless you have been blessed to track down the films of Suzuki Seijun, you will never, ever, have seen anything like this before. It has a plot – it is a gangster film – a hero, his girl and villains. There are betrayals and gunfights. You still wonu0026#39;t have seen anything like this before. Imagine A BOUT DE SOUFFLE, shot in the style of UNE FEMME EST UNE FEMME, with a mixture of Leone, Welles, Melville, THE AVENGERS and Fulleru0026#39;s HOUSE OF BAMBOO. Not even close.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe basic plot concerns the title hero, a gangster trying to go straight. His boss and father-figure (this is a very Oedipal film, but the concept, with its many variations, is stretched to absurd breaking point), also a former gangster, is being pushed around by some extraordinarily attired hoods. The hero has a girl who sings big Michel Legrand-type numbers in a huge, blazingly colourful art deco/Busby Berkeley/Jean Cocteau-type nightclub. Because the hero is a maverick, he lies low for a while (i.e. drifts), but is followed by a hitman. All converges in a fairly predictable fashion.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eTo appropriate the ad, Plot is Nothing, Style is Everything. If a studio with big resources is, as Welles claimed, a u0026#39;toy setu0026#39;, then Seijun is the class freak. The monochrome gangster world is blown apart by shocks of colour, be they dazzling primary hues, or deliberately effete pastels. This serves to upturn the black and white ideology of the gangster genre. The men are all snarling and macho, but the hero sings and whistles, like the Dukeu0026#39;s singing cowboy; the lead villain wears loud red shirts and sports a ridiculous moustache. There is even room in the plot for a gag about hairdryers.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eLike in Godard, the crucial plot elements are roundly mocked; the seemingly major event of the hero being captured by and subsequently evading the police is as if filmed by an inept child. The group violence scenes are messy, like brawls at a childrenu0026#39;s party. There is even a bar-room brawl in a Western saloon in a Japanese gangster movie.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eMirroring Melvilleu0026#39;s heros, the hero aspires to aloof self-sufficiency, but he is constantly undermined by the film. Whole chunks of story donu0026#39;t make sense. The vertiginous editing is like the maniacal string-pulling of a puppeteer ,and there is a strong Brechtian feel to the film, with frequent breaks for cheesy song; impossible sets; unmotivated lighting; some of the most bizarre and beautiful camera movements in film.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAll this stylistic bravura could be monotonous if it wasnu0026#39;t grounded intellectually and emotionally. There are some really beautiful oases of grace amid the violent mayhem. The film is a firm attack on the assumptions of genre, conformity, sterile repetition, linked to conformity in Japanese society at large, and big business in particular. Like 50s melodramas, the colour schemes, lighting and composition reflect the state of mind of the characters. The lengthy snow sequence is worthy of Joyceu0026#39;s u0026#39;The Deadu0026#39;.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003enWhen it comes to Japanese cinema, I know weu0026#39;re all supposed to bow down to Kurosawa and Ozu, but Iu0026#39;ll take the absolutely hatstand Seijun anyday. Breathtaking genius.”