Saint Ange – Haus der Stimmen (2004)

39KSaint Ange – Haus der Stimmen: Directed by Pascal Laugier. With Virginie Ledoyen, Lou Doillon, Catriona MacColl, Dorina Lazar. In 1958, in the French Alps, a young servant, Anna Jurin, arrives at Saint Ange Orphanage to work with Helena while the orphans are moved to new families. Anna, who is secretly pregnant, meets the last orphan, Judith, left behind because of her mental problems, and they become closer when Anna finds that Judith can also hear voices and footsteps of children. Anna investigate the place trying to disclose the secret about the invisible children.

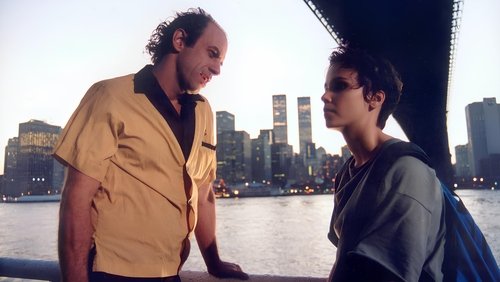

“When upon its theatrical release I first saw u0026#39;An Unmarried Womanu0026#39; I thought it brilliantly captured the feminist outlook – not the radical feminist viewpoint but the growing awareness of the vast majority of ordinary women of new modalities for living. I just saw it again on DVD and my first impression of the film holds up. But through my having aged my perspectives have matured, and now I also find u0026#39;An Unmarried Womanu0026#39; to be perhaps the finest capturing of 1977u0026#39;s zeitgeist – but only the zeitgeist of upper middle class New Yorkers (Mazursky better captured the wider 70u0026#39;s zeitgeist in u0026#39;Harry and Tonto).u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eHere Mazursky shows that, whatever else he is accused of being or doing or not-doing (with which I donu0026#39;t always agree or disagree), is a thoughtful director taking a good, long, realistic look at this drama and at more than just its central character. I liked that some scenes ran on for a bit longer than some people find necessary or comfortable, because this is how lifeu0026#39;s scenes often play out beyond oneu0026#39;s wanting them to end swiftly and tidily: indeed, the slight overrunning of some scenes contributes what today might be called u0026quot;value-addedu0026quot; realism to u0026#39;An Unmarried Woman.u0026#39; After all, Erica has, involuntarily, been thrust into a new life in which sheu0026#39;s not at ease in every one of its developing, novel situations.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe saxophone score – probably considered hip in 1977 – is today often more than a trifle annoying; but then it could be said that the score is part of the filmu0026#39;s capture of the 70u0026#39;s zeitgeist: like all decades the 70u0026#39;s had its annoyances (not the least of which was the dismal monotony of disco, and all those decor-saturating browns, olives (avocado it was called!), honey-golds, and tawny oranges).u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe cinematography here is quite good, nicely tailored to the filmu0026#39;s intimate subject, situations, and relationships. Throughout the acting is uniformly good; Jill Clayburghu0026#39;s effort here is, and will remain I expect, a cinema original and classic. I especially enjoyed – not when I first saw the film but much more so now in 2006 – Cliff Gormanu0026#39;s portrayal of self-satisfied, on-the-make Charlie. Andrew Duncan in the minor role of Bob lends great verisimilitude with his pre-u0026quot;hair systemsu0026quot; comb-over but especially with the touch of about-to-be-over-the-hill despair in Bobu0026#39;s attempt to bed Erica; Bob demonstrates that most men in that decade, beginning as they were to be flummoxed by emerging liberated women and feminism, still clung to the suddenly obsolescent notion that a divorcée would and should be eager to remarry in order to traditionally assure her security and peace of mind.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAt my first viewing I agreed with what Tanya, Ericau0026#39;s therapist, said to Erica about guilt being a manufactured, unnecessary emotion. But a good many more years of living have taught me that guilt is not manufactured, and that without it a person is doomed to emptiness and isolation, and a society is doomed to decadence, and even to barbarism. Rather Tanya should have held that guilt is natural, and that it is oneu0026#39;s mature management of it that enables one to distinguish, in oneself and in others, venality and narcissism from generosity of spirit.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eu0026#39;An Unmarried Womanu0026#39; still stands on its own – more as a socio-cultural than as a cinematic landmark. Itu0026#39;s that rare kind of film thatu0026#39;s worth watching every five or ten years, if only to help us to recall where weu0026#39;ve come from, and to help us to profit from, or to enjoy, a sense of where we might be going.”