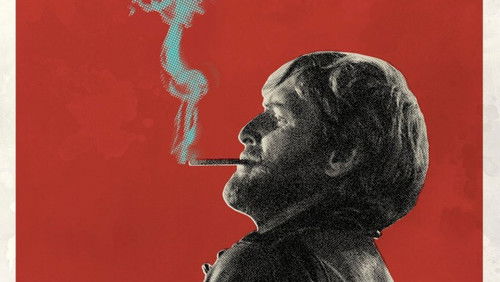

Soredemo boku wa yattenai (2006)

16KSoredemo boku wa yattenai: Directed by Masayuki Suô. With Ryô Kase, Asaka Seto, Kôji Yamamoto, Masako Motai. A young man is falsely accused of molesting a high-school girl on a train. He is arrested and charged, and goes through endless court sessions, all the while insisting that he is innocent.

“Two ironies attest to critiquing this film a year after it was submitted to the 2008 Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. First of all, this year, 2009, saw the Japanese feature Okuribito scoop that very award, a film directed by a man whose early credits include a long-running u0026#39;train molesteru0026#39; series, a sniggering look at the titillation gained from the sport of groping vulnerable-but-loving-it females on crowded commuter trains.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe second irony is that the Japanese Supreme Court recently overturned a guilty verdict on a man convicted of such a crime, citing the lack of evidence and due procedure on the part of police and prosecutors.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eOkuribitou0026#39;s debt to Suou0026#39;s film is tenuous, but the Supreme Court decision seems unlikely had Sore Demo not been made. The film highlights the primitive and highly dubious procedures that infest the Japanese judicial system, where habeas corpus is trampled upon and a benign and apathetic populace conspire by neglect in the crushing of innocents. The scale of the molester problem is apparent to any visitor to these shores who spends time on commuter trains – Women Only carriages are now the norm at rush-hour, a far cry from the halcyon days previously celebrated by the director of Okuribito, when u0026#39;how to molestu0026#39; programmes were broadcast on mainstream TV channels. Times have changed, and how.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSuo elects to tell the tale as an Educational film, attempting to edify his audience on the corruption of the Japanese judiciary from the base assumption that they know nothing. Such stylistics have come unstuck before in Nihon no Ichiban Kuroi Natsu, where the didactic tone fails to encapsulate the social ramifications of the material it addresses. But Suou0026#39;s film does not go off on that tangent, presenting as its innocent in need of education a single man falsely accused in a groping incident. He is a decent, loved man who finds circumstances piling up against him in a country he previously, naively, accepted as fundamentally good. Ryo Kase does excellent work as meek Teppei, who puts up with his treatment initially unaware of the hole that is being dug for him. His resolve not to opt for the easy u0026#39;guiltyu0026#39; verdict that will secure quick release is a deep moral core by contrast lacking in the police, judges, fourth estate and even his own solicitor.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe preaching can be a bit heavy-handed at times, and the film is at least 30 minutes too long. Some dubious side characters are overdrawn, such as an effeminate cell-mate thrown on stage to provide giggles and more leadership for Teppei. Such small qualms aside, this movie is an epochal event, an important film, that highlights an incredible, mean-spirited flaw in Japanese society, that the recent Supreme Court decision may finally relegate to history.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eSuou0026#39;s direction is spare and unobtrusive, his actors given space to reveal the consequences of such judicial brutality, which they do with aplomb. Brave, important film-making, that history will take note of.”