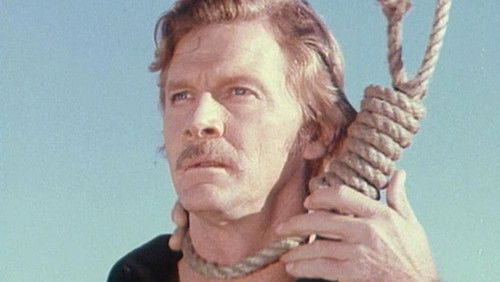

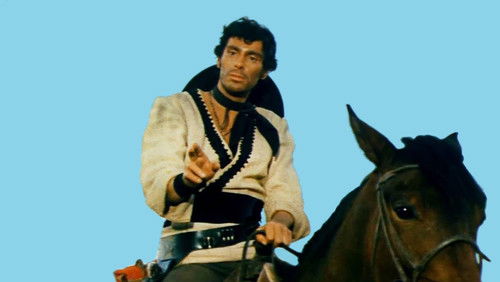

Die vier Söhne der Katie Elder (1965)

11KDie vier Söhne der Katie Elder: Directed by Henry Hathaway. With John Wayne, Dean Martin, Martha Hyer, Michael Anderson Jr.. Ranch owner Katie Elder’s four sons determine to avenge the murder of their father and the swindling of their mother.

“Beset by production difficulties and largely ignored by critics upon release, this is a film that, like its star, has grown better with age. Director Hathawayu0026#39;s open-air style perfectly suits the expansive nature of the material, which by todayu0026#39;s standards seems almost leisurely. In fact Sergio Leone acknowledged this fact when he greatly reworked the opening station scene as the beginning of Once Upon a Time in The West/Cu0026#39;era una volta il West (1969). (He also had his heroine arriving at his own Clearwater station later.) Elmer Bernsteinu0026#39;s score is a standout, recalling his achievement on The Magnificent Seven (1960). There are several scenes which gain immeasurably from his masculine music, which ranges from the grand celebratory mode of the main theme to some suitably subdued and menacing cues for the final showdown.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eA convalescent Wayne plays the returning gunfighter John Elder, summoned by the death of his mother. Bewigged, paunchy, and slightly wheezy, the recently de-lunged actor still acts an imposing head of the Elder clan. He finds himself leading a dysfunctional family, united at first by grief, then the clumsy depredations of Morgan Hastings (an excellent James Gregory) who has swindled his way into possessing the family land. Together with memories of the late Katie Elder herself, like an American monument, Wayneu0026#39;s presence dominates the film. Recognising this, Hathaway uses it to great advantage with the first view of his star, perhaps Wayneu0026#39;s most impressive screen entrance since that in Stagecoach of 26 years earlier. As Katie is buried, in long shot, we take in an overview of the cemetery with its cluster of mourners, A massive rock formation overshadows the land. After a few seconds, a small detail catches the eye high up in a cleft. The camera cuts closer, and we think we recognise the figure. Cut again, and it is shown to be the watching John, irresistibly solid and still. At this stage in his career Wayne so easily assumes the permanence and grandeur of landscape that the iconic nature of this moment is accepted by the viewer without question.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThis is last time in his career that Wayne is so emphasised. Twice in Katie Elder the director takes the opportunity to film his star u0026#39;doing the walku0026#39; his tall frame strolling purposefully towards the camera, intent on action. In later films (such as Hathawayu0026#39;s own True Grit (1969)) such virile ruggedness is replaced by hard-bitten cantankerousness, more in keeping with the actoru0026#39;s advancing age. It was more the rule too, in Wayneu0026#39;s later career, for seriousness to be replaced by knockabout humour, reaching a zenith in the boisterous McClintock! (1963). In Katie Elder, many of the interior scenes between the brothers are marked by such elements of genial horse play, culminating in a fist fight in which John Elder crashes through a door. Outside they present more of a unified force, optimistically dubbed by Hastings u0026#39;the Elder Gangu0026#39;. Showing this is more difficult than it seems, and fortunately Hathaway keeps matters under control. Moments of broad comedy, like Tom (Dean Martin) auctioning off his glass eye, are not too distracting and often provide a contrast to more serious moments (Curley threatening Matt with gunplay). The banter between the Elder sons also serves to unify the siblings in the most natural way, and establish relationships, even if some of the camaraderie is hard won. In particular one wishes that the two older brothers had more to say to each other, or shared some scenes alone – especially given the on-screen rapport Martin effortlessly created a few years earlier when he worked with Wayne in Rio Bravo (1959).u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAs the villain of the piece, Hastings has an emphasised affinity with a special firearm. His armament enthusiasm recalls some of the baroque arsenals appearing in some spaghetti Westerns of the time, where the traditional six shooter was replaced by ever more fancy weapons. At the start of the film Hastings has already hired Curley, a heavy dressed all in black in very traditional fashion. This range thug is played well by George Kennedy, and the scene where he is clubbed in the mouth by Wayne is often cited by viewers as one of the most memorable. In fact, so effective is Curleyu0026#39;s suggested brutality that one wishes more could have been made of a man who says ominously u0026#39;I donu0026#39;t care what I have to do, as long as I get my moneyu0026#39;. Curley and Wayne needed more of a showdown to make their moral antipathy pay dividends, and the viewer is disappointed that this doesnu0026#39;t eventually occur. It is one of the weakness of the film that the villain meets his demise so casually, a victim of crossfire rather than a deliberate showdown. As Hastingu0026#39;s son Dave, Dennis Hopper performs adequately. One feels he would have been better cast as the younger Elder brother, with more to do. In contrast to Kateu0026#39;s oft-stated warmth towards her absent sons, Hastingu0026#39;s treatment of his sibling is cold and uncaring. If the less experienced face of Jeremy Slate had been cast as his son, the gun loveru0026#39;s cruelty would have been even more damning. As it is, Hastingsu0026#39; attitude towards Dave is left largely unexplained, although predictable enough.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eApart from the casting and music, much of the pleasure of the film springs from the mise-en-scene familiar to those who enjoy the big 50u0026#39;s and 60u0026#39;s Westerns. The geography of Clearwater for instance, so effortlessly established in the early scenes; the interior of Katieu0026#39;s pioneer cabin, or the gunfight by the river. It is also a reminder of a lost time in Westerns, when an ever reliable Wayne confronted frontier trouble, with none of the moral complications suggested by the contemporary work of a Peckinpah or Leone. Like the simple pleasures Mrs Elder found in her beloved rocking chair, this is a production which has been continually revisited by fans since the initial release, and will continue to be so.”