For Ever Mozart (1996)

43KFor Ever Mozart (1996). 1h 24m | Not Rated

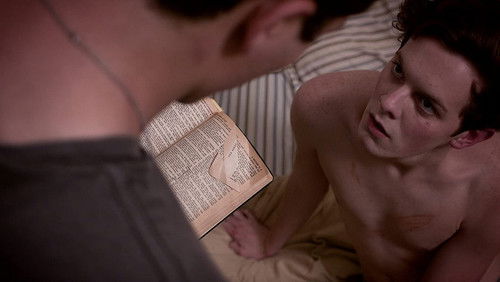

“Pointless, the negative reviews damn this film. Yes, but only if we arrive here expecting a narrative separated from the life and legacy of its author. But if we have apprenticed in Godardu0026#39;s work and stuck with him, for better or worse, the inscrutable film is a rich text which can be read, to various effects.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe prophecies of the ancient oracle at Delphii hinged on the presence of the coma, moving the coma to the next word the entire sentence attained new meaning. The prophecies were oral however, which means the coma was a later adoption, by the receiver. Moving the figurative coma here we get different interpretations, both meaningful in their contradiction.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eA couple of young French intellectuals with aspirations for political activism embark on a trip to Sarajevo to stage a Musset play (or make a film, Iu0026#39;m not clear on this). Along with them tags halfheartedly their old uncle, a theatrical writer. When we see him sitting on a bed, a grizzly crone wearing a hat, ruminating quotes from a book in hand, we know who he is or is meant to be. In the 60u0026#39;s Godard spoke through radical, troubled youths like these, now he feels separate, of an older, bitter generation who fought its struggles and stepped aside, to let the following generation take its stab at the political chimera.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eTwo instances in the film, figurative comas, are important in this aspect.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eOne is the arrival of our youths at Sarajevo, criminal no manu0026#39;s land torn by a bloody civil war. Youth radicals from Western countries in the 60u0026#39;s enlisted in various revolutionary causes like the PLO, what used to be anticipated hopefully is now met by Godard with cruel, bitter disillusionment. Our protagonist are not greeted as brother guerillas come to join a cause that matters, instead theyu0026#39;re summarily arrested. The dream of revolution is here crashed under torture, ridicule, ingloriously digging their own graves. A corrupt Yugoslavian general presides over the aimless carnage, now and then a soldier routinely makes the rounds of mortars planted in the middle of nowhere, casually firing rounds at unseen enemies. But is that failure one of ideas or people, weu0026#39;ll have to decide as viewers.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe other, personally poignant for Godard, is the uncle who abandons these youths before Sarajevo, running off with a truck of film equipment to make a film. Shifting the coma here we may read this variously, as Godard recognizing with the hindsight old age permits the folly of what is to come, or as Godard reflecting with some regret and shame that he wasnu0026#39;t more involved in that cause in his time and merely made films.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eWhatever meaning we choose to ascribe, Godard here doesnu0026#39;t follow the revolution, he openly abandons it (which he did more than a decade ago, perhaps only now mustering the courage to clearly show on film). But, having withdrawn from the dream that used to matter, where does he turn next to devote himself? u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eWe may know the answer from Godardu0026#39;s career, the films he chose to make, the subjects that troubled him next. On the set of the film-within which the uncle assists in making, he stages a second absurdist comedy, this time a biting satire of the debasement of filmmaking. He establishes this with running gags. Cinematographers always an f-stop off, walking around trying in vain to get light readings, a megalomaniac director who demands for his shots more water in the sea.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eBoth these points, politics and cinema, are met with disillusionment. If nothing exists after the end and this life is all that matters, as weu0026#39;re told in the film, then the life weu0026#39;re shown here doesnu0026#39;t amount to much, the struggle is solitary and disheartening. In many respects this is a continuation of Week End where in the end of it youths marched off with joyous clamor and violence to a revolution, only now Godard wastes no cheap shots mocking the bourgeois and includes himself and the revolution in the recipients of his ire. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAt filmu0026#39;s end, Godard, the uncle, is sitting alone with a book, overhearing a rehearsal of Mozart in a different room (u0026quot;too many notes, they saidu0026quot;). The film then elucidates, bitterly or smartly, the events and decisions that brought him to where he is now, in 1996.”