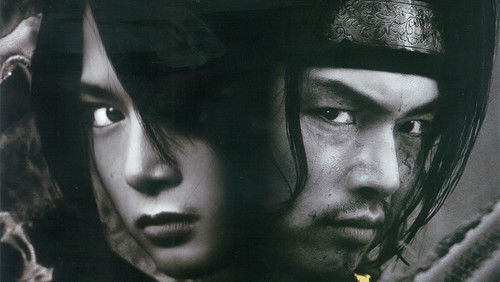

Je tu il elle (1974)

18KJe tu il elle (1974). 1h 26m

“Chantal Akerman had a stretch of time in the 1970u0026#39;s where she made her mark with fully experimental films. Some of them had a narrative, like Jeanne Dielman, and others were more like elongated postcards like News From Home or Hotel Monterrey, but they all had a distinctive mark, with long takes, obsessively long, and characters doing physical actions that are akin to ritual or just apart of a repetitive nature. I, You, She, He is a really revolutionary piece of work, though I canu0026#39;t say I really u0026#39;enjoyedu0026#39; it exactly. Itu0026#39;s a film that is made to provoke the audience, into discussion or just a reaction. I can only imagine what it must have been like to see this in a theater, where half the audience might get up in the first ten minutes, and the rest stayed with equal enthrallment and confusion at what they were seeing. Itu0026#39;s also quite naked, literally at times, about a search for (sexual) identity.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAkerman plays Julie, though weu0026#39;re never revealed that is actually her name, and for the first half hour of this 86 minute film, sheu0026#39;s in her room. Thatu0026#39;s it. She writes a letter, or a few letters, rewrites them, moves around furniture, eats sugar, eats more sugar, spill some sugar and spoon by spoonful puts the sugar back in the brown bag, and then gets naked and roams around the room. You might have heard the expression with an u0026quot;art-houseu0026quot; film that itu0026#39;s u0026quot;like watching paint dry.u0026quot; With this film, itu0026#39;s hard to exaggerate that claim enough. Shots last for minutes, and Akerman is often sitting either in obsessive detail of what sheu0026#39;s doing, or not really doing anything at all, like in a trance, with her narration coming up dutifully explaining exactly what is happening or will happen on screen.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eBut if you stick with it, and being a fan of Jeanne Dielman I knew this was how Akerman likes to film in a patient poetic style, it starts to show a pattern. Julie isnu0026#39;t just doing nothing, but sheu0026#39;s doing MUCH of nothing, obsessively, over and over, with the letters, the sugar, the furniture, her own body. And just when itu0026#39;s getting too long going, as if Akerman knows how the audience is feeling, Julie finally leaves the room. From here it becomes a two-part road trip. First she hitchhikes and is picked up by a truck driver. His scenes start slow, but at least thereu0026#39;s more on the soundtrack (music, audio from a TV, other cars), and it leads up to an un-erotic but fascinating scene where the driver forces Julie to give a hand-job. He then gives a monologue about his wife and kids and driving while aroused. Why not? Itu0026#39;s an amazing list of things said, and acted well enough.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe second part is the most surreal, but also the most heartfelt. Julie meets up with a Girlfriend at her place, and at first they eat. But then comes a very long scene of lovemaking. Again, do shots go on too long, or are they just right for the rhythm Akerman is reaching for? If you think the former, then probably youu0026#39;ve already tuned out or turned off the film. For the latter, it is just about right, and by now Akerman has gone to a kind of alienating apex. Itu0026#39;s hard to identify with Julie, but some of her concerns, like finding a place, people to love or be with, something to do worthwhile, do resonate, and the subtext is thick with ideas and methods. The approach is precisely feminist, much more so than anything else I can think of from the period, where the technique, the u0026quot;performancesu0026quot; (vacant/naturalistic as they are), and the heart in its poetic intent speak about a womanu0026#39;s nature to be unsatisfied, and searching for something, a longing, a person, sex, anything. That itu0026#39;s Akerman herself in the role, often naked and open, is startling.”