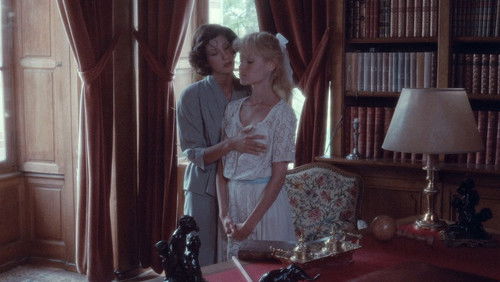

Tausendschönchen – kein Märchen (1966)

21KTausendschönchen – kein Märchen: Directed by Vera Chytilová. With Ivana Karbanová, Jitka Cerhová, Marie Cesková, Jirina Myskova. After realizing that all world is spoiled, Marie and Marie are committed to be spoiled themselves. They rip off older men, feast in lavish meals and do all kinds of mischief. But what is all this leading to?

“The opening of u0026#39;Daisiesu0026#39; features a montage of two subjects very familiar to 1966 Eastern Bloc film audiences: work and war, as shots of an industrial machine alternate with views of rubbling city from an airplane bomberu0026#39;s point of view. These are masculine subjects in a very masculine culture. Or they seem to be. The machine features a circular mechanism, and represents repetition, but also productivity, and might be said to represent female principles, whereas the war footage is of pure destruction. The heroines of u0026#39;Daisiesu0026#39; embody both these gender-specific realms, and manage to create something new. They are idle, but, like George Costanza, their indolence depends on relentless invention. They are destructive, but out of the destruction they produce something new. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eu0026#39;Daisiesu0026#39; was a product of the Czech New Wave, but seems a million miles away from its most famous contemporaries, the films of Menzel and Forman. These latter, though liberal and anti-totalitarian, were artistically conservative – deliberately humanist works, where u0026#39;realu0026#39;, psychologically plausible characters exist in u0026#39;realu0026#39; places, and every narrative progression makes logical sense. If they seem u0026#39;timelessu0026#39; to us now, it is because they didnu0026#39;t truly engage with their own times.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eAnd, of course, they were male. Where they seem closer to the 19th century novel, or classic Hollywood cinema, Chytilovau0026#39;s peers are the great European modernists, Godard, Paradjanov, Makajev, Rivette, or the plays of Ionesco. Where Forman and Menzel framed their illusions of realism in formal coherence, Chytilova revels in formal instability. These arenu0026#39;t psychologically plausible characters in a cause-and-effect universe. We first meet the two Maries after the opening credits, and their automaton gestures, with accompanying sound effects, continue the movement of the machine. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe plot basically consists of the girls trying to chat up old men whou0026#39;ll feed them, but what they really do is make a nonsense of plot. The recurring motif is the posy of roses worn by Marie II, and thrown by her to further the story – we remember the nursery rhyme u0026#39;a ring a ring of rosies, a pocketful of posies, a tishoo, a tishoo, we all fall downu0026#39;. And everything falls down here, in a game where the rules have splintered and fragmented. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe film mixes monochrome, colour, and unstably tinted scenes. Sequences that begin u0026#39;sensiblyu0026#39; are broken down, by slapstick, changes of register, u0026#39;impossibleu0026#39; changes of location or physics, or are turned from natural scenes into the robotic movements of a clockwork toy going out of control. This disruption has a theoretical point – in one scene, the girls find their bodies cut up as they find their identities dissolved by conflicting desires, social expectations and representations. In another, they wander around a dream space, wondering why people pay no attention to them, realising that u0026#39;logicallyu0026#39;, they mustnu0026#39;t exist, because Western culture has no place for them. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eJust as they parody the notions of work and war (in the climactic food orgy, martial army music soundtracks a cake fight), so these sprites play with and destroy the assumptions of Western humanism, its claims to adequately represent u0026#39;realityu0026#39;, especially in a time of such bewildering, radical change, as in the 1960s. They do to cinema what Ionesco did to literature, cut it into shreds. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe whole thing plays like parody Godard, with Marie II as Anna Karina, with meaningful conversations about love accompanied by the girls cutting up sausages and bananas: the butterfly sequence is a wicked lampoon of u0026#39;Vivre sa Vieu0026#39;. Where Godardu0026#39;s heroines remained fixed and stared at, the two Maries laugh, look, escape, see their frame and break it, insist on their body as something more than an object, something they can play with themselves. u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eNot even the heroinesu0026#39; liberating subversivess is fixed – their mindless appetite is punished as often as their formal iconoclasm is celebrated. But for all its theoretical rigour, u0026#39;Daisiesu0026#39; never sacrifices its sense of humour – I first saw it when I was ten, and loved it for its slapstick fun, its narrative unpredictability, its playful soundtrack, and its tireless visual invention. I still love it now.”