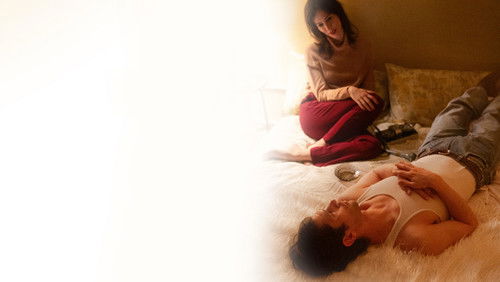

Amores perros (2000)

54KAmores perros: Directed by Alejandro G. Iñárritu. With Emilio Echevarría, Gael García Bernal, Goya Toledo, Álvaro Guerrero. A horrific car accident connects three stories, each involving characters dealing with loss, regret, and life’s harsh realities, all in the name of love.

“There is a character in u0026#39;Amores perrosu0026#39; who looks like Karl Marx. He is a tramp and an assassin, a good bourgeois who one day, Reggie Perrin-like, abandoned his family, and, un-Reggie Perrin-like, joined the Sandanistas in an effort to create a better world, earning 20 years in prison for his troubles. Walking the streets with a creaky cart and a gaggle of mangy dogs, he was found by the policeman who jailed him, who gave him a dingy place to live, food, and the odd, non-official contract.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eEl Chivo is the soul of the film, the missing link, both in appearance (a man called u0026#39;The Goatu0026#39;, who has rejected the civilities of society and lives a beast-like existence with his dogs, amongst the ruins of civilisation), and narrative function. With intricate structure, u0026#39;Amores perrosu0026#39; tells three stories, one of underclass Mexican life, where survival depends on what New Labour calls u0026#39;illegal economiesu0026#39; (dog-fighting, bank-robbing etc.), where bright young women are stifled and degraded by thoughtless pregnancies and brutal marriages, where single mothers depend (and usually canu0026#39;t depend) on shiftless sons for subsistence; and this worldu0026#39;s mirror opposite, the world of the media, of celebrity, of models and magazine editors, of daytime TV, perfume advertising campaigns and bright apartments. Family life is central here too, although in this case it is torn apart by more pleasanntly bourgeois ailments like ennui and dissatisfaction.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThese two stories are mediated by the narrative of El Chivo, the man who left one of these worlds for the other, but who still negotiates the two, through his search for the daughter he left as a toddler, and in his u0026#39;jobu0026#39;, wiping out businessman. If Mexico is emerging as part of the super-confident globalism of high-capitalism, than El Chivo is the grizzly sore thumb, the ex-Sandinista, the Marx lookalike, the man who said no, the drop-out, the forgotten, the depleted spirit of the Left, happily killing and torturing the servants of the new economic regime.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThere is something Biblical about his hirsute ascetism too, presuming to judge the u0026#39;Cain and Abelu0026#39; half-brothers, one an adulterer, the other with a contract out on his sibling, another example of family gone badly wrong. This, the bleak funeral and grave scenes, and Octaviau0026#39;s functional crossing himself every time he passes an icon on the landing, are the sole residual elements of religion in a society once ostentatiously religious.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eExcept for the director. Like Paul Thomas Anderson in u0026#39;Magnoliau0026#39;, although to a less self-conscious degree, Gonzales Inarritu is the God of his film, intricately creating the structure that links his characters and their different environments. These are negative connections, however, which work against the idea of coherent meaning in life – contact usually results in destruction (physical, material, spiritual), or diminishing.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eHe is also an Old Testament god, punishing those who would get too confident with their future plans or their seemingly inviolable present success – the gains of capitalism are prey to the violent whims of chance: Gonzalez Inarritu doesnu0026#39;t need frogs to shake a rigid society or mindset.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eMoral change is linked to physical change – being beaten up, losing a leg, cutting hair. The punning title, with its reference to the dog-eat/fight-dog nature of modern life, and its general unsatisfactoriness, also gives the film its Biblical feel, the idea of Mexico as an asphalt desert, or a rubbish heap, with all these scrawny mutts scavenging the remains.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eu0026#39;Amores perrosu0026#39; shares the sickly, bleached near-monochrome look of many recent crime films, like u0026#39;Chopperu0026#39; or u0026#39;Bleederu0026#39;. But where the heightened mise-en-scene in those works were expressionistic projections of their protagonistsu0026#39; psychosis, here itu0026#39;s part of a controlling world-view, the universal consciousness that creates, connects and destroys.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003enThe three stories, though connected narratively and symbolically, are mutually distinct – the first is an exhilirating mix of violent gangster film and frustrated romance; the second is like a short story (the screenwriter is a novelist), a figurative plot where movement is through image, symbol and idea, rather than film narrative; the third is a kind of spiritual journey, with an appropriately Biblical (or Wim Wenders-like) openness.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eu0026#39;Amores perrosu0026#39; is not quite as amazing as its admirers claim – it says more about contemporary cinema that a film only has to hold your interest for it to be a masterpiece – but it is consistently enthralling, and, despite all the stylistic tics and brutal violence, bracingly humanist.”