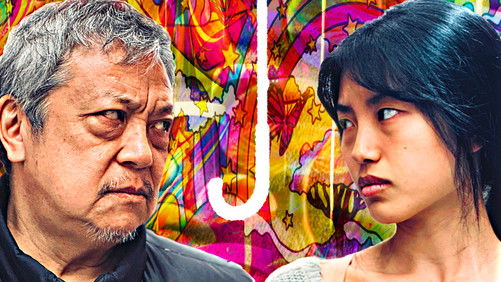

Ginrei no hate (1947)

69KGinrei no hate: Directed by Senkichi Taniguchi. With Toshirô Mifune, Takashi Shimura, Yoshio Kosugi, Akitake Kôno. Three bank robbers, Eijima, Nojiri, and Takasugi, flee the police and escape into the mountains. At an inn high in the Japanese Alps, Eijima and Nojiri encounter a young woman and her father, as well as Honda, a mountaineer. The inn folk do not realize their guests are wanted criminals and the visitors are treated with great kindness. Honda volunteers to lead them over the mountains, but Eijima’s paranoia endangers all of them as they make the perilous trip.

“This peculiar romantic crime drama would probably be hailed as a classic if it were widely seen today, although itu0026#39;s not that tremendous; still, itu0026#39;s a deliberately unusual piece of work, and a generally neglected piece of Akira Kurosawau0026#39;s filmography (as indeed are the majority of those pictures he wrote but did not direct, an alarming number of which have never even been shown outside Japan). It marks the formal debuts of Senkichi Taniguchi as director and Akira Ifukube as composer, but in the long run itu0026#39;s very much more a Kurosawa movie, shot through with his accustomed humanity, and full of surprises. Especially interesting is the way Takashi Shimurau0026#39;s criminal character develops, starting out proudly savage and then against all odds becoming a tender person, who ultimately cannot bear to kill the man who is loved by the woman HEu0026#39;S in love with … because he canu0026#39;t stand the idea of hurting her. Toshiro Mifuneu0026#39;s character, by contrast, seems redeemable at the start but grows increasingly evil — not at all what the filmmakers suggested at the start, and not at all expected. The film also boasts an astonishingly restrained performance by Yoshio Kosugi, who rarely met a piece of scenery he didnu0026#39;t like to gnaw upon, but who is remarkable here. Setsuko Wakayama and Kokuten Kodo are also superb; this is probably one of the only pictures that gave Wakayama a chance to shine, as for whatever reason she never became a major star in Japan.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eThe snowbound location photography is excellent (much of the picture was drawn upon director Senkichi Taniguchiu0026#39;s own considerable experience as a mountain climber), and while Akira Ifukubeu0026#39;s score is almost too energetic for its own good — he clearly thought that his first time out he ought to be scoring every different scene with a separate leitmotif, and GODZILLA fans might be amazed to hear his first version of the famous u0026quot;underwater balletu0026quot; music from that original 1954 film already in here (more conservative viewers who avoid monster movies might have also happened to hear the identical music in THE BURMESE HARP) — Ifukube underlines the drama beautifully, and in the lengthy sequences that are without dialogue, he tells us most eloquently what the characters are feeling. When the elegy kicks in under Shimurau0026#39;s reappearance over the cliff, itu0026#39;s a heartbreaker. And yet thereu0026#39;s hardly any music at all in the first hour, unusual for a film of any type at the time.u003cbr/u003eu003cbr/u003eItu0026#39;s not quite a masterpiece, but THE END OF THE SILVER MOUNTAINS is essential viewing for anyone who cares about Kurosawa, Mifune, Shimura, Ifukube, or indeed everyone who worked on this movie, and very clearly cared about it a lot.”